Cyrus The Great

Southern Iran, near modern Shiraz.

In a region the Greeks called Persis, a vassal king was about to flip the script on empire-building. Cyrus II didn't just want to conquer, he wanted people to actually want to be conquered. And somehow, it worked.

Author’s Note ✍: you’ll see the term vassal king several times in this article. A vassal king is basically a king who owes his allegiance to a more powerful king, emperor, kingdom, etc.

For three thousand years, from the first Sumerian city-states to the fall of Assyria, Eastern empires had followed a basic pattern

Conquer through military force

Hold the empire through terror or administrative control

Extract wealth through tribute and taxation.

Some empires, like Babylon, were more sophisticated in their methods. Others, like Assyria, were more brutal. But the fundamental model was the same.

Cyrus the Great didn't invent a completely new system. But he combined elements in ways no one had attempted at this scale, and he made choices that seemed counterintuitive to every other king.

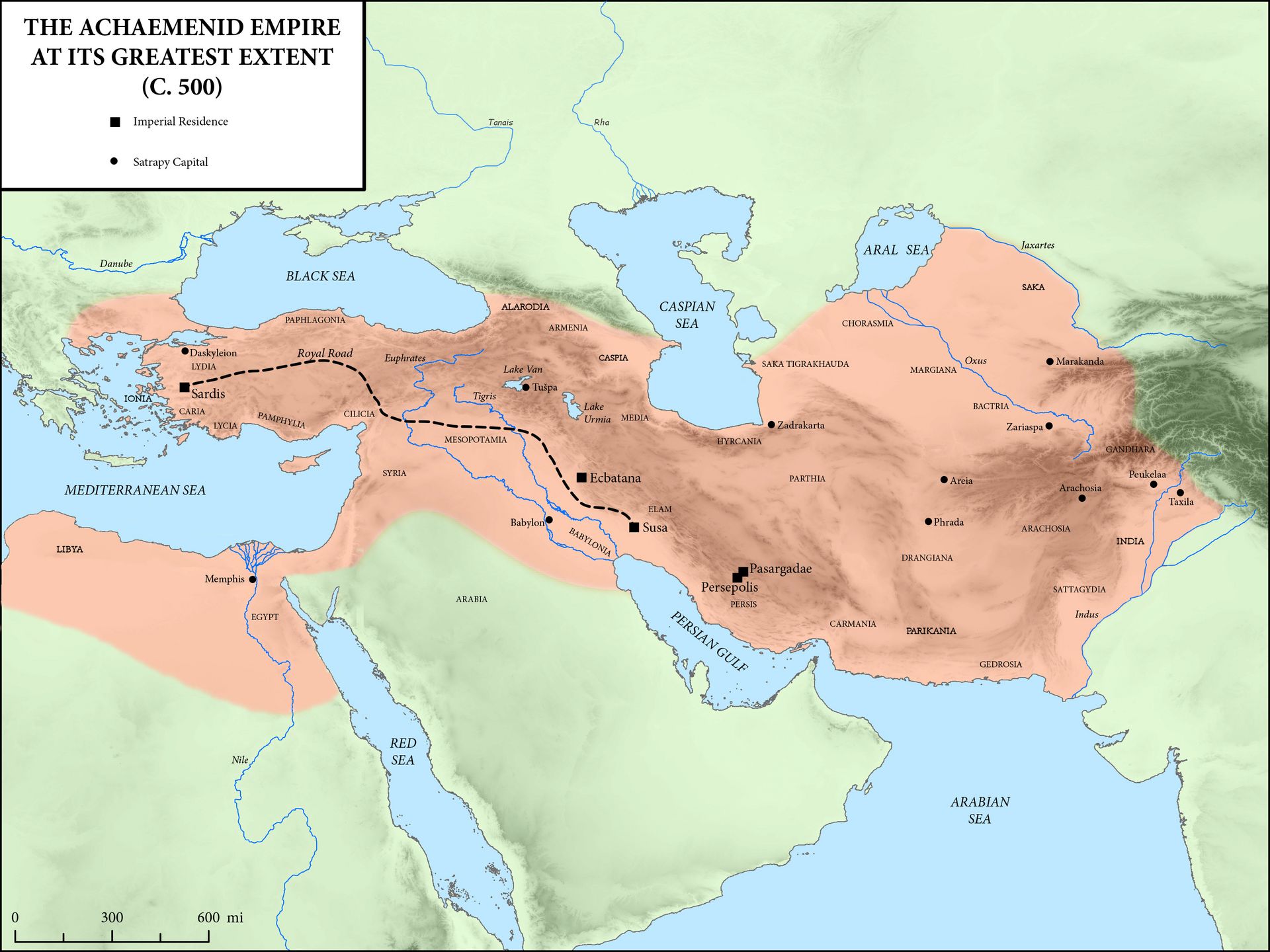

The result was an empire that lasted longer, controlled more territory, and integrated more diverse peoples than anything that had come before.

The story of how that happened starts with geography, dynasty, and a calculated gamble that could easily have ended with Cyrus's head on a spike.

The Iranian Plateau

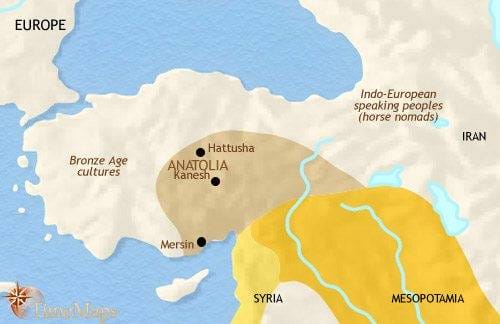

The landscape that produced Persia was fundamentally different from the river valleys of Mesopotamia.

The Iranian plateau is high, dry, and broken by mountain ranges. It's harder country than the fertile plains of Babylon, less productive agriculturally, more dependent on long-distance trade and herding animals (think goats, sheep).

The people it produced were correspondingly different, harder, more mobile, organized around tribal confederations rather than city-states.

This region had been the homeland of the Medes, who had helped Babylon destroy Assyria.

After 612 BC, the Median Empire controlled everything from the Zagros Mountains to Central Asia. They had organized various Iranian tribes into something resembling a centralized state, though it remained more loosely structured than Mesopotamian empires.

Within the Median sphere of influence, Persis was a client kingdom, important enough to deserve attention, not powerful enough to threaten independence. The Achaemenid dynasty that ruled Persis traced its lineage back for generations, claiming ancient royal descent, but that mattered little in practical terms. They paid tribute to the Median king. They provided troops when requested. They were vassals.

Then Cyrus II took the throne around 559 BC, and everything changed.

The Rebel with Two Crowns

Cyrus's background gave him a unique position. His father, Cambyses I, was the Achaemenid king of Persis. His mother, according to Herodotus, was the daughter of the Median king Astyages. This made Cyrus both Persian royalty and Median royalty, a bridge between two Iranian dynasties, with potential claims to both thrones.

Whether Herodotus's genealogy is accurate remains debated by historians. What's clear is that Cyrus used claims of Median connection to legitimize his later actions. He wasn't just a rebel overthrowing his overlord. He was a member of the royal family correcting a dynastic irregularity.

Around 553 BC, Cyrus stopped paying tribute to the Median king. This was rebellion, pure and simple. Astyages marched south with a Median army to crush this upstart vassal and remind the Persians of their place.

And then something extraordinary happened: the Median army defected.

The sources disagree on exactly why. Some suggest Astyages was unpopular with his own nobility. Others claim Cyrus had been cultivating relationships with Median commanders for years. Herodotus tells a story about Astyages having tried to kill Cyrus as a child due to prophetic dreams, creating resentment among Median nobles who saw this as unjust.

Whatever the cause, the result was clear. The Median army switched sides. They declared for Cyrus. And instead of crushing a rebellion, Astyages found himself overthrown by his own troops.

Cyrus marched into the Median capital of Ecbatana in 550 BC. And here's where his approach became distinctive. He didn't destroy the city. He didn't execute the Median nobility. He didn't dismantle the Median administrative structure. Instead, he declared himself the successor to the Median throne, positioned himself as uniting Persian and Median peoples under a joint empire, and retained many Median officials in their positions.

This was calculated brilliance. Rather than creating a Persian Empire ruling over conquered Medes, Cyrus created a Medo-Persian Empire where both peoples had buy-in. The Medes weren't defeated subjects, they were junior partners in an expanded imperial project. This gave Cyrus access to Median cavalry, administrative expertise, and territorial control without having to fight for it.

The model he would apply to every subsequent conquest was established in this first rebellion: integration over domination, co-option over destruction, inherited legitimacy over imposed rule.

The Western Campaigns

With Media secured, Cyrus controlled the Iranian plateau and the territories stretching toward Central Asia. But the real wealth lay west, in Anatolia and Mesopotamia, and the real threats came from established powers who saw a unified Medo-Persian state as dangerous.

King Croesus of Lydia ruled in western Anatolia, controlling the Greek cities of the Ionian coast and sitting on legendary gold deposits that made him the richest king in the known world. Croesus looked at the sudden emergence of Persian power and decided he needed to act before Cyrus became unstoppable.

According to Herodotus, Croesus consulted the oracle at Delphi, asking whether he should attack Persia. The oracle responded that if he crossed the Halys River (the border between Lydia and Median territory), he would destroy a great empire. Encouraged, Croesus invaded in 547 BC.

The oracle was right. Croesus did destroy a great empire…his own.

The details of the campaign are contested, but the outcome isn't. Cyrus responded to the Lydian invasion with devastating effectiveness. He pursued Croesus back to the Lydian capital of Sardis and besieged it. The city, supposedly impregnable, fell in just fourteen days. Croesus was captured.

What happened next became part of Cyrus's legend. Instead of executing Croesus, Cyrus kept him as an advisor. Instead of completely destroying Sardis, he left the city standing and installed a Persian governor. Instead of massacring the population or deporting them, he allowed them to continue their lives under new management.

The Greek cities of the Ionian coast, seeing which way the wind was blowing, mostly submitted without fighting. Some resisted and were conquered, but even then, the Persian treatment was measured. Local governments remained largely intact. Religious practices continued unchanged. Economic life went on. The Greeks found themselves part of a Persian Empire that seemed less interested in controlling every detail of their lives than in collecting taxes and maintaining strategic loyalty.

The Eastern Frontier

While the western campaigns get most attention from Greek sources, Cyrus also campaigned extensively in Central Asia. We know far less about these campaigns because they didn't affect the Greek world and thus weren't documented by Greek historians. But they were crucial for Persian power.

Central Asia provided resources the Persian heartland lacked: horses, particularly the breeding grounds for cavalry mounts; manpower from tribal confederations; and control of trade routes connecting the Mediterranean world to India and China. Cyrus spent years securing these territories, and the campaigns were apparently more difficult than his western conquests.

He would eventually die on one of these eastern campaigns in 530 BC, fighting against the Massagetae, a nomadic people north of the Oxus River. The circumstances are disputed, Herodotus tells a dramatic story about a warrior queen named Tomyris who defeated and killed Cyrus in revenge for her son's death. Other sources give different accounts. What's certain is that even Cyrus, with all his success, couldn't fully pacify the Central Asian steppe peoples.

But by the time of his death, Cyrus controlled territory from the Aegean Sea to Central Asia. He had built the largest empire the world had yet seen. And he had done it in less than thirty years.

The Cyrus Cylinder and the Question of Intent

In 1879, archaeologists excavating in Babylon found a clay cylinder inscribed in Akkadian cuneiform. It's now known as the Cyrus Cylinder, and it contains Cyrus's account of his conquest of Babylon (which we'll get to shortly). More broadly, it articulates a governing philosophy that seems radically different from anything that came before.

The cylinder describes Cyrus as chosen by Marduk, the chief Babylonian god, to restore proper worship and return displaced peoples to their homelands. It presents him as a liberator rather than a conqueror, someone restoring justice rather than imposing foreign rule. It has been called the world's first declaration of human rights, though that's a significant overstatement.

The question historians debate is: was this genuine policy or sophisticated propaganda?

The cynical interpretation is that Cyrus simply recognized that allowing local autonomy and religious freedom was cheaper and more effective than Assyrian-style terror. It cost less to let people worship their own gods than to impose Persian religious practices. It was easier to collect taxes from prosperous, willing subjects than to extract tribute from resentful, impoverished populations through force. Cyrus's "tolerance" was just smart imperial management dressed up in noble language.

The more generous interpretation is that Cyrus actually believed in a governing philosophy that recognized the value of diversity and local autonomy. That he saw empire as a system of mutual benefit rather than pure extraction. That he understood power flowed more reliably from legitimacy than from force.

Pierre Briant, argues for a middle position. Cyrus's policies were probably pragmatic in origin but became systematized into a coherent governing philosophy. Whether he started from cynical calculation or genuine idealism mattered less than the fact that he created institutional structures that incentivized tolerance and local autonomy.

What's undeniable is that the system worked. Persian rule generated less resistance than Assyrian or Babylonian rule had. Subject peoples prospered under Persian administration. And that prosperity translated into resources the Persian state could mobilize when it needed to.

The Satrap System

The administrative structure Cyrus developed became the foundation of Persian governance for two centuries. The empire was divided into provinces called satrapies, each governed by a satrap, essentially a provincial governor with significant autonomy.

This wasn't entirely new. The Assyrians and Babylonians had used provincial governors. But the Persian system gave satraps more independence. They controlled local military forces. They administered justice according to local customs and laws. They collected taxes but had discretion in how those taxes were raised. They were expected to maintain order and provide troops when the central government required them, but otherwise, they governed as they saw fit.

This created a system that could accommodate enormous diversity. A satrap in Egypt could govern according to Egyptian traditions. A satrap in Ionia could work within Greek political frameworks. A satrap in Babylonia could operate through the old Mesopotamian temple and scribal bureaucracies. The Persian Empire didn't require cultural uniformity—it just required political loyalty and tax revenue.

The risk, of course, was that powerful satraps might become independent. Later Persian history is full of satrapal revolts and attempted breakaways. But Cyrus and his successors developed mechanisms to limit this risk. Royal inspectors—"the king's eyes and ears"—traveled throughout the empire monitoring satraps. The satrap controlled provincial forces, but the king maintained a separate imperial army directly loyal to the throne. And perhaps most importantly, satraps were usually appointed from Persian nobility who had their own estates and interests in the empire's stability.

Infrastructure of Empire

Cyrus understood that controlling territory meant connecting it. Under his rule and that of his successors, Persia built the ancient world's most extensive road system.

The Royal Road stretched from Sardis in western Anatolia to Susa in southwestern Iran—roughly 1,500 miles. Way stations were established every fifteen miles or so, providing fresh horses for royal messengers. A message could travel the entire length in about a week, a speed of communication that wouldn't be matched until the modern era.

Herodotus, who was generally critical of Persian power, couldn't help but be impressed: "Neither snow nor rain nor heat nor gloom of night stays these couriers from the swift completion of their appointed rounds." This description would later be adapted as the unofficial motto of the United States Postal Service, though most people don't realize they're quoting a Greek historian's description of Persian infrastructure.

The roads served multiple purposes. They facilitated trade, allowing merchants to move goods safely across vast distances. They enabled military mobilization, letting the Persian army respond quickly to threats anywhere in the empire. They projected power, demonstrating Persian capacity to reach any province. And they gathered information, allowing the central government to know what was happening in distant territories.

This infrastructure was expensive, but it was the kind of investment that paid long-term dividends. A merchant who could safely trade from India to Greece would pay taxes throughout his journey. A province that knew the royal army could arrive quickly was less likely to rebel. A satrap who knew inspectors might appear unexpectedly was more likely to remain honest.

Religious Policy

Perhaps nothing distinguished Persian rule more clearly from previous empires than religious tolerance. Assyria had no consistent religious policy beyond occasionally destroying temples of rebellious peoples. Babylon elevated Marduk but generally accommodated other gods. Persia went further, actively supporting local religious institutions.

Cyrus's proclamations consistently present him as chosen by local gods to restore proper worship. In Babylon, he claimed Marduk had selected him. In Judah, the biblical book of Isaiah calls him "the Lord's anointed" the only foreign ruler given this title. When he conquered a region, he typically patronized local temples, returned sacred objects that previous empires had stolen, and funded religious festivals.

This wasn't secularism or anything like modern religious freedom. The Persians had their own religion, probably an early form of Zoroastrianism, though the details are debated. But they didn't require subject peoples to abandon their own gods. Multiple religious systems could coexist under Persian rule as long as they didn't threaten political stability.

From a purely pragmatic standpoint, this made sense. Religious institutions were often the most stable and influential organizations in ancient societies. Making them allies rather than enemies was smart politics. A priest telling his congregation that the Persian king had been chosen by their god was worth more than a garrison of troops.

But the policy also created genuine loyalty. When you've spent generations being conquered by empires that destroyed your temples and mocked your gods, an empire that respects your religious practices feels like liberation, even if you're still paying taxes to a foreign power.

The Economics of Empire

Persian taxation was reportedly more systematic and less arbitrary than what had come before. Instead of tribute demanded at a king's whim, provinces paid fixed taxes assessed based on productive capacity. The historian Herodotus provides numbers for how much each satrapy paid annually though historians debate their accuracy, the existence of such specific amounts suggests systematic assessment.

The empire used a standardized coinage system, making trade easier. The daric, a gold coin bearing the image of the Persian king, became trusted currency throughout the Near East and Mediterranean. When merchants from Greece to India would accept your currency, you know you've achieved economic credibility.

Persia also invested in large-scale infrastructure beyond roads. Irrigation projects expanded agricultural productivity. Harbor improvements facilitated maritime trade. The empire even attempted to dig a canal connecting the Nile to the Red Sea, anticipating the Suez Canal by twenty-five centuries.

The project was never completed, but the ambition reveals how Persians thought about empire: as an economic system that should generate prosperity, not just extract wealth.

This created a virtuous cycle. Prosperous provinces paid more taxes without resistance. Those taxes funded infrastructure that made provinces more prosperous.

Merchants who profited from Persian peace became invested in the empire's stability. Even people who didn't particularly like foreign rule recognized that Persian administration made them wealthier than independence might.

The Last Obstacle

By 540 BC, Cyrus controlled everything from the Mediterranean to Central Asia except for one major power: Babylon.

Babylon was ancient, prestigious, and wealthy. It sat astride the crucial trade routes connecting the Persian Gulf to Syria. It had the cultural authority that came from millennia of Mesopotamian civilization. And it was, at least in theory, still a great military power.

But Babylon had problems Cyrus could exploit. The current king, Nabonidus, had spent much of his reign living in Arabia rather than in Babylon itself, pursuing what seemed to be eccentric religious interests. He had elevated the moon god Sin over Marduk, enraging the powerful Babylonian priesthood. The economy had stagnated as Persian control of trade routes reduced Babylon's commercial advantages.

Most importantly, Nabonidus had become deeply unpopular with the very people who should have been his base of support. The priests wanted a king who would respect traditional Babylonian religion. The merchants wanted economic stability. The people wanted competent leadership. Nabonidus provided none of these.

Cyrus recognized the opportunity. Babylon could be conquered militarily, but that would be costly and would require garrisoning a hostile city. Better to be invited in. Better to position himself not as a conqueror but as a liberator, someone restoring proper order to Babylon.

So Cyrus waited, applied economic pressure, conducted a sophisticated propaganda campaign, and let Nabonidus's unpopularity do most of the work for him.

The Model That Worked

Before we get to Babylon's fall, which deserves its own telling, it's worth understanding why Cyrus's model succeeded where Assyrian brutality had ultimately failed.

Empires face a fundamental challenge: how do you govern people who don't want to be governed by you? The Assyrian answer was terror—make the cost of resistance so high that people submit out of fear. This worked for three centuries but ultimately created a situation where every subject people wanted revenge and the empire had no allies when crisis came.

Cyrus's answer was different: make Persian rule attractive enough that resistance seems pointless. Let people keep their religions, their languages, their local governance structures. Protect trade. Build roads. Fund temples. Provide security. In exchange, pay taxes and provide troops when requested.

This was very similar to Rome hundreds of years later.

Modern parallels aren't hard to find. The British Empire at its height offered trade access and security. The European Union offers economic integration and free movement. American hegemony after World War II offered market access and military protection. All of these systems worked better than pure coercion could have, though none achieved the longevity of the Persian model.

The question is whether soft power can survive setbacks. Terror collapses immediately when the military fails, Assyria proved that. But does integration-based empire last when prosperity falters or security weakens?

Persia would face that test repeatedly over two centuries. But first, Cyrus had one more conquest to complete. The ancient city that had started the cycle of Mesopotamian empire, that had survived 900 years of occupation, that had helped destroy Assyria and built a second empire.

Babylon would fall without a battle. And in doing so, it would demonstrate just how different Cyrus's empire really was.

Next: The night Babylon opened its gates to Cyrus, ending the Babylonian Captivity and reshaping how the ancient world understood power, legitimacy, and the relationship between conquerors and conquered.